Meta-form: Cities, Metaphors, and Sustainability

Last updated 2 years ago

If a designer takes inspiration from nature on form alone, they will design for you a plastic plant— an object which looks like the real thing with none of its function, destined for the landfill where it will destroy that which inspired it. However, if this same designer took inspiration instead from the systems of nature, they might design something which grows, something that is self-sustaining, something that doesn’t end up in that landfill but instead is repurposed or “decomposed” in some form. The world, unfortunately, is full of plastic plants.

Part 1: Form

And the metaphor of the “city as an organism”

If you have ever been in the heart of a city, you may have an inkling of what it means for a city to be “alive.” And no, it is not the skyscrapers, nor famous buildings or destinations, for these would be nothing without people. It is the people and systems, the change and growth, the space in-between buildings that give a city its character.

The metaphor of the city as an organism has influenced greatly the way we design and think about the built environment. The metaphor between cities and humans can be traced back all the way to Ancient Greece (Omid, 2017, p. 74). Architects have long seen the city as a living organism. Some of the more contemporary advocates include Le Corbusier, Kenzo Tange, and Frank Lloyd Wright, some of the most influential architects of the 20th century. (p. 103; 114)

“All architectural products, all city neighborhoods or cities ought to be organisms. This word immediately conveys a notion of character, of balance, or harmony, of symmetry.” (Le Corbusier, 1967, p. 147)

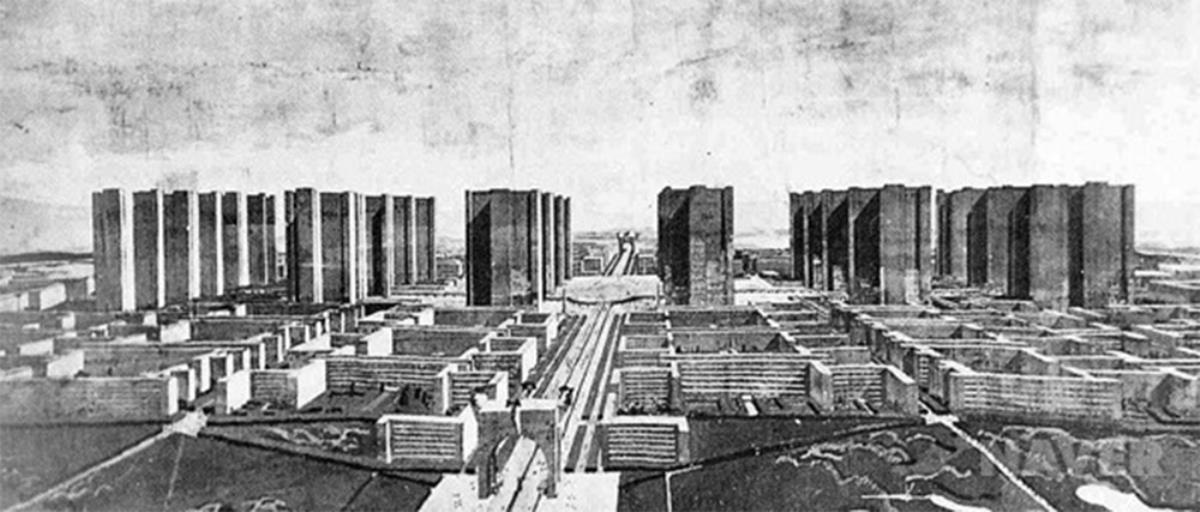

Le Corbusier’s vision stretched far beyond a single building or home, which he would describe as the ‘cells’ of a city (Le Corbusier, Urbanisme 1924/1971, p. 73). He envisioned what he called the Ville Radieuse, or Radiant City, a city of three million inhabitants radiating out from a central core, with large arteries forming the city’s circulatory system. This city would be separated into different districts of residential, business, education, manufacturing, just like the organs of a body are separated out into specialized functions.

“The plan spliced together an extendible linear city with an abstract image of a man: head, spine, arms and body. The skyscrapers were arranged at the head, and the body was made up of acres of à redent housing strips laid out in a stepping plan to generate semi-courts and harbours of greenery containing tennis courts, playing fields and paths” (Quoted in Jo and Choi, 2003)

When I look upon this image I do not get the feeling of anything “alive” about this city. Le Corbusier took his inspiration from form, the basic and repetitive building blocks of the cell and the separation of organs and used those to design not a ‘plant’ but a ‘plastic human’ in the shape of a city, a frankenstein monster that no strike of lightning could bring alive. Yet the idea lived on, influencing a generation of architects and urban planners, and resulting in some of the most disastrous public housing projects in history. Two of the most famous examples, Pruitt-Igoe (Fiederer, 2017, ¶ 4) and Cabrini-Green (Austen 2018, ¶ 11) were directly inspired by the plans of Le Corbusier.

“Le Corbusier’s utopian radiant city of highways and high-density tower blocks became a widely imitated formula for post-war residential development by public and private sector builders. A corporate urban landscape, the product of an increasingly corporate society” (Ley, 1987)

Part 2: Systems + Sustainability

And the application of ecological thinking

In On the Origin of Species, Charles Darwin provided overwhelming amounts of evidence to back up the claims of evolution. The book represented a widespread shift away from the religious beliefs surrounding species at the time. Around the same time, cities underwent a similar shift but in the opposite direction away from a city which evolves to one that is planned, bringing the birth of urban planning as a formal discipline.

I do not propose that we forgo the planning of cities, that would be unsustainable, but rather I think that we need to adapt towards a more ecological approach to thinking about and designing our built environments. Cities produce over 60% of all greenhouse gas emissions and consume 78% of the world’s energy (UN Habitat, 2019); ecological perspectives are not only important but necessary in today’s climate crisis. And not by approaching the design of forms through a metaphor wide open for (mis)interpretation, but through a shift in thought which may well pave the way for a new species of urban planner.

Fritjof Capra writes that “we can design sustainable societies by modelling them after nature’s ecosystems.” He describes eight concepts as a starting point for design: networks, nested systems, interdependence, diversity, cycles, flows, development, and dynamic balance (Capra, 2005). None of which play a role in Corbusier’s plan. Capra also advocates for six different shifts in thought; for example to shift from seeing “the parts to the whole,” which starkly contrasts Corbusier’s microscopic view of cells to design the macro-object of a city.

Capra’s suggestions are corroborated by dozens of other systems and ecology thinkers, and designers. Sterling for example provides this list of approaches to ecological thinking that move away from traditional analytical and problem-solving approaches to thought. (Sterling, 2009)

However no work explores the idea of “life” in architecture and urban planning in as much depth as Christopher Alexander’s four-volume essay, The Nature of Order. In the first volume he introduces 15 principles of “life” in design: (Alexander, 2002)

Now you may be thinking, why then all these rules? If ecological thinking and design tries to move away from rules, analysis, and problem solving (Sterling, 2009) then why does each thinker, each scientist, each designer have their own list of rules? Corbusier too formulated his own rules for architecture and urban planning and followed them quite rigidly, how is this different?

I give these examples from Capra, Sterling, and Alexander because they are not in fact rules at all but frames of mind. A rule can be applied without consideration, but a frame of mind is a way of being, questioning, and looking at the world. Rules are easy to teach, but a frame of mind has to be lived. History is full of modernist, postmodernist, high-tech, modern, and contemporary architecture; however if these perspectives are embodied by architects and urban planners then at last we will move into a new era which I would call, humanist.

Part 3: Case Study

Beneath my feet stands one of the most prime examples to demonstrate not only post-modern architecture as a result of ecological thinking, but also its opposite, modern economically driven development taking inspiration from the ideals of Le Corbusier. At the very heart of Vancouver, the battle ground where these two approaches glare face to face, across an inlet but a world apart: False Creek North, and False Creek South.

Having lived on the south side of False Creek all my life, over the years I have noticed many positive qualities of the urban design which have affected my own life:

- The enclave in which I live encircles a central courtyard area which helps build community and facilitate connection between neighbours (and you always see children playing)

- The street and place names hint back to False Creek’s history and industrial past, sometimes serving as interesting conversation topics (Spyglass, Leg-in-boot Square, Sawcut)

- Each enclave of buildings is unique in its architecture, materials, and colours. Specifically the colour of the roofs becomes a part of one’s identity as a resident

- False creek is designed around walking and biking. It is rare to see many cars, and the parking lots are hidden beneath units or under walkways

- Although we are located at the heart of the city, we are separated from the main roads by a small forested walkway. It feels very quiet and communal and not at all like a big city until you walk a few blocks up to broadway

When I delved into researching the history of the False Creek area I was pleasantly surprised to find all these points were specifically addressed and designed to create a more ecological and human-scale living environment:

“To enhance community, many of the enclaves were circular with a common open area at the core. There were marked variations between enclaves in construction materials and design, creating a diverse set of forms, the objective being a more personalized landscape which would support subgroup identities.” (Ley, 1987)

The Electors Action Movement (TEAM) founded in 1968, led to much of what makes Vancouver different to other north american cities. With campaign phrases like “the livable city” and “for people, not concrete and asphalt”. It is because of this movement that Vancouver does not have freeways running through the city, they expanded parks, and down-zoned inner-city districts to exclude high-rise towers. They also planned and designed the reformation of False Creek South. (Ley, 1987)

“The underpinning ideology of development represented the fusion of aesthetics, ecology and social justice” (Ley, 1987)

The design of False Creek South ticks all the boxes of the ecological approaches to design thinking I discussed in part two. A large focus of the plan was the idea of diversity, one of the principles of ecosystems discussed by Capra. Diversity of lifestyles, materials, income levels, and going beyond simply a residential plan with an elementary school, community centre, theatre stages, an art school named after some famous artist, and a public market selling local and artisanal goods.

It owes to the effectiveness of the ecological frame of mind, and the open and participatory design process exercised by the committee that their design choices are immediately felt and experienced everyday over 40 years later.

Across the water lies our antithesis, False Creek North, lined with high-density condominiums, a casino, and a stadium. Designed under modernist ideals and profitability. It’s nice, there’s parks I’ve never strolled in, and benches I’ve never sat in, surrounded by tall buildings I’ve never lived in, with little escape from the bustle of the city. I bike through there sometimes on my way to Stanley Park.

Conclusion

I have tried my best to write this essay with an ecological perspective in mind. Constructing three diverse sections each bringing their own perspectives, and looking holistically at architecture, ecology, and the heart of Vancouver itself. I spend time to appreciate the aspects of ecological design in the False Creek neighbourhood, as well as critique the faux-ecological metaphor used by Le Corbusier. Together these come together to form… my intention. Having a single point wouldn’t be very holistic, instead I hope this essay provides you with new perspectives, and sets you on a path to discover your own ecological frames of mind.

Adopting an ecological perspective takes lived experience, but in uncovering the history beneath my feet I have discovered that I have been living it this whole time.

Bibliography

Alexander, C. (2002). The Nature of Order: The Phenomenon of Life. Routledge.

Austen, B. (2018, February). The Towers Came Down, and With Them the Promise of Public Housing. The New York Times Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/06/magazine/the-towers-came-down-and-with-them-the-promise-of-public-housing.html

Capra, F. (2005). Speaking Nature’s Language: Principles for Sustainability. In Stone M. K. (Ed.) Ecological Literacy: Educating Our Children for a Sustainable World.

Fiederer, L. (2017, May). AD Classics: Pruitt-Igoe Housing Project / Minoru Yamasaki. ArchDaily. Retrieved from https://www.archdaily.com/870685/ad-classics-pruitt-igoe-housing-project-minoru-yamasaki-st-louis-usa-modernism

Jo, S., & Choi, I. (2003). Human Figure in Le Corbusier′s Ideas for Cities. Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering, 2(2), 137–144. doi:10.3130/jaabe.2.b137

Le Corbusier. (1967). The Radiant City. New York: The Orion Press.

Le Corbusier. (1971). The City of Tomorrow and Its Planning (3rd ed.). London: The Architectural Press (Original work published Urbanisme 1924).

Ley, D. (1987). Styles of the times: liberal and neo-conservative landscapes in inner Vancouver, 1968–1986. Journal of Historical Geography, 13(1), 40–56. doi:10.1016/s0305-7488(87)80005-1

Omid, V. (2017). The Role of Human Metaphors on Urban Theories and Practices (Doctoral Thesis, Technische Universität Berlin). Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.14279/depositonce-6630

Sterling, S. (2009). Ecological Intelligence. In The Handbook of Sustainable Literacy (pp. 77–83).

UN Habitat. (2019). United Nations Climate Change Summit 2019. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/cities-pollution.shtml